cyber/fiber

cyber/fiber (2021-) is a project exploring the links between computation and knitting. The work involves different types of interdisciplinary research: Material research, utilizing a modded or hacked KH-930e knitting machine connected to a computer running open source software from All Yarns Are Beautiful (AYAB), and revisiting and re-figuring the intertwined histories of textile production and computing to imagine different technological futures.

This body of work aims to trouble the distinction drawn between engineering and craftwork. Craftwork is a form of engineering, requiring similar sets of skills and training. However, gendered notions around what computing expertise looks like has conferred value on different forms of labor. These distinctions are a product of distinct historical and social transformations. For instance, the hand-woven core rope memory in early computers was created by physically weaving software by hand. Highly skilled weavers and craftworkers, most of whom were women whose labor was undervalued, worked in Massachusetts to weave the core rope memory that powered the early Apollo Guidance Computer.

In this work, I also look at how the history of textile production and labor can teach us lessons about the future. The Luddites famously resisted the transition to factories by systematically destroying the stocking frame machines that had replaced traditional knitting techniques, and with them the knitting guilds who had historically cultivated consensus around the quality of knitwear for centuries.

In my work, I attempt to explore these histories through a process of unwinding, untangling, pulling and stretching, knitting and unraveling. I approach knitting as a technique that can help us reimagine or re-figure different technological futures. How can we imagine futures that are more relational, connective, and centered around care?

This body of work aims to trouble the distinction drawn between engineering and craftwork. Craftwork is a form of engineering, requiring similar sets of skills and training. However, gendered notions around what computing expertise looks like has conferred value on different forms of labor. These distinctions are a product of distinct historical and social transformations. For instance, the hand-woven core rope memory in early computers was created by physically weaving software by hand. Highly skilled weavers and craftworkers, most of whom were women whose labor was undervalued, worked in Massachusetts to weave the core rope memory that powered the early Apollo Guidance Computer.

In this work, I also look at how the history of textile production and labor can teach us lessons about the future. The Luddites famously resisted the transition to factories by systematically destroying the stocking frame machines that had replaced traditional knitting techniques, and with them the knitting guilds who had historically cultivated consensus around the quality of knitwear for centuries.

In my work, I attempt to explore these histories through a process of unwinding, untangling, pulling and stretching, knitting and unraveling. I approach knitting as a technique that can help us reimagine or re-figure different technological futures. How can we imagine futures that are more relational, connective, and centered around care?

Works

the air moves in to fill the spaces where my body's been (2024)

Garments serve as an interface: They act as a kind of scrim, separating our body from the bodies around us. This sweater is a prototype for a live performance exploring the spaces that exist between bodies.

The sweater contains a detachable “patch,” knitted using hand manipulated stitches that produce a 3D ruching effect. The patch contains a proximity sensor and battery pack wired up to a FLORA, an Arduino-compatible microcontroller. The proximity sensor allows me to track my proximity to other bodies over time.

Knit on a knitting machine with wool yarn.

the air moves in to fill the spaces where my body's been (2024)

Garments serve as an interface: They act as a kind of scrim, separating our body from the bodies around us. This sweater is a prototype for a live performance exploring the spaces that exist between bodies.

The sweater contains a detachable “patch,” knitted using hand manipulated stitches that produce a 3D ruching effect. The patch contains a proximity sensor and battery pack wired up to a FLORA, an Arduino-compatible microcontroller. The proximity sensor allows me to track my proximity to other bodies over time.

Knit on a knitting machine with wool yarn.

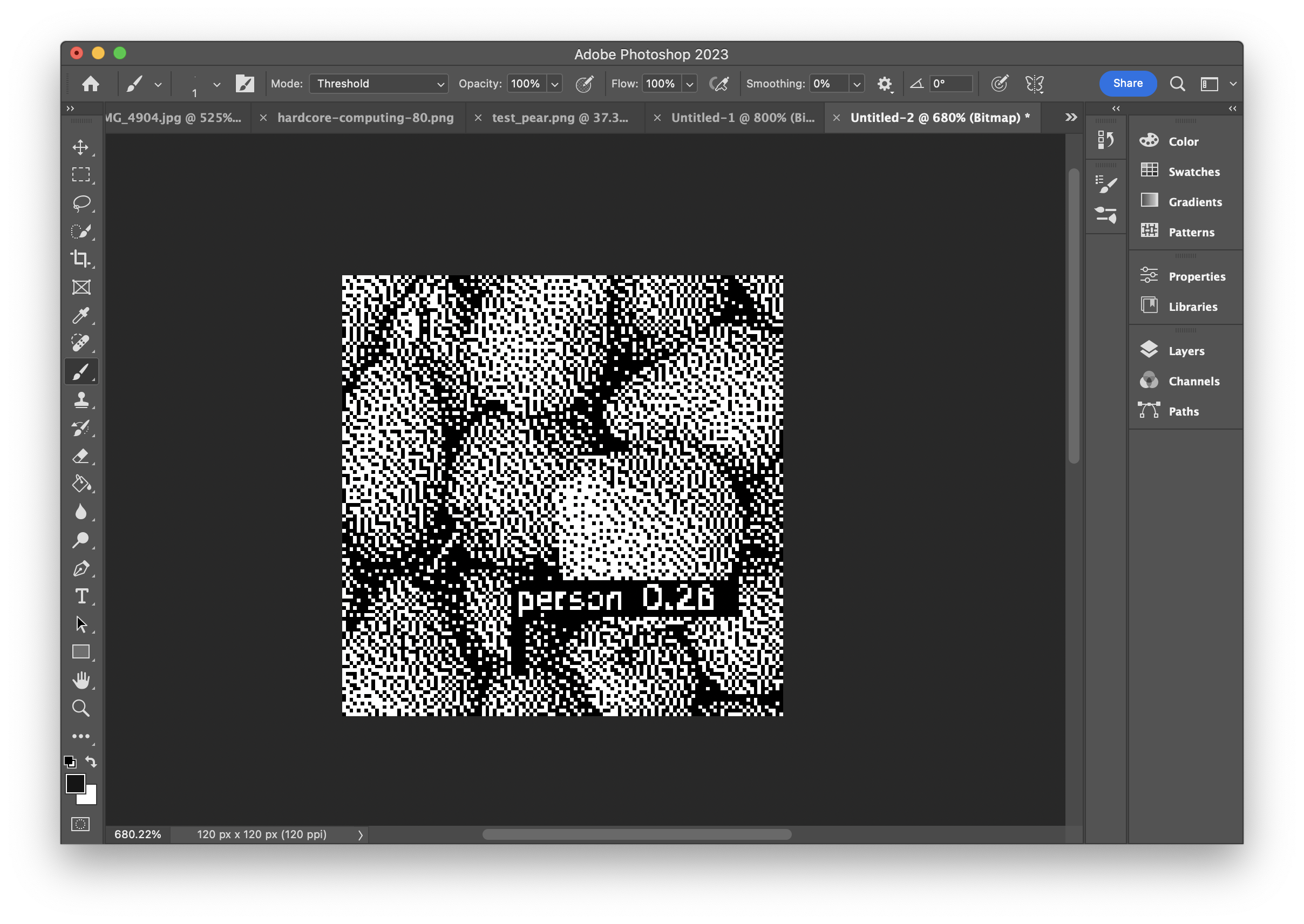

Seeing (Pears) Like a Computer (2024)

This piece is a reflection on what it means to be seen and classified through the eyes of a machine. The sweater highlights errors made by the image classification model Ultralytics YOLOv8, a state-of-the-art machine learning (ML) model used to classify and label images.

The title references the work of James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State, which emphasizes the universalizing gaze of large systems that are designed to identify, sort, and categorize people and bodies for the purpose of exercising control and enforcing normative values.

When I ran an image of pears harvested from my pear tree through the model, it incorrectly identified one of the pairs as a “person” with a 0.26 confidence threshold. I later learned that this particular model struggles to identify small objects or objects that are clustered together.

Knit on a knitting machine with wool yarn, naturally dyed with bark from a pear tree in my backyard.

This piece is a reflection on what it means to be seen and classified through the eyes of a machine. The sweater highlights errors made by the image classification model Ultralytics YOLOv8, a state-of-the-art machine learning (ML) model used to classify and label images.

The title references the work of James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State, which emphasizes the universalizing gaze of large systems that are designed to identify, sort, and categorize people and bodies for the purpose of exercising control and enforcing normative values.

When I ran an image of pears harvested from my pear tree through the model, it incorrectly identified one of the pairs as a “person” with a 0.26 confidence threshold. I later learned that this particular model struggles to identify small objects or objects that are clustered together.

Knit on a knitting machine with wool yarn, naturally dyed with bark from a pear tree in my backyard.

You can watch a 2024 artist talk I gave on the topic titled Knitting with machines: Imagining softer futures through ‘string figures.’